Trick | Tease

PHILIP JOHNSON BERNARD TSCHUMI

“I hate vacations. If you can build buildings, why sit on the beach?”

“To really appreciate architecture, you may even need to commit a murder”

I have chosen two figure-heads whose work has been endorsed over many generations in the field of architecture. Of course, they have been celebrated on countless occasions from the highest academic institutions, to the CEO’s of international corporations and granted audiences to distinguished heads of state all around the world. Both Philip Johnson and Bernard Tschumi have stood and survived the test of time as gate-keepers to a profession that has often [since antiquity] being sanctified as equal to the powers of the Divine!

Trickery here is a license that I have granted myself as a catalyst to antagonise, to provoke, or even to ruffle the feathers [so to speak] that both architecture and the architect [with a small ‘a’] is often a vocation that is overly idolized in terms of its moral or ethical correctness.

I very much doubt that to be the case.

And here’s why…

- Christian Bjone

“I never thought I would be an architect. And that is why I had such a strong attraction to Modern, because I could play at architecture but not have to be one.”

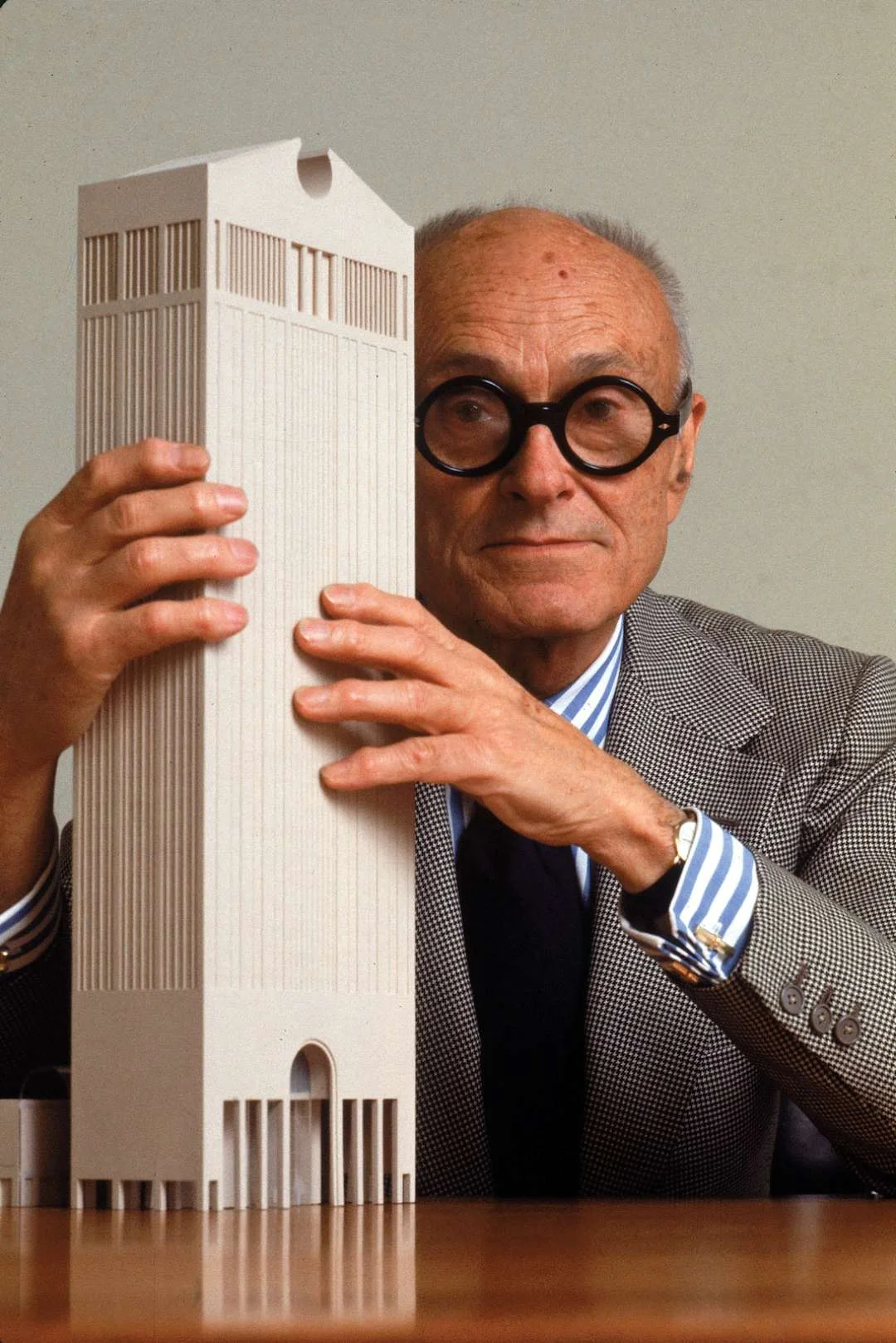

Here is a legend, an architectural canon who has been called or labelled as a copy, a fake, a cheat and even a whore! These are harsh accusations for an individual, who had apprenticed with Mies in the execution of the Seagram Building, curated two world acclaimed exhibitions at the MoMA, an impassioned supporter of Nazism, and recipients to both the AIA gold medal and the inaugural lifetime Pritzker Architecture Prize.

Raised with a silver spoon in his mouth, Johnson was already a full-pledged millionaire when he enrolled into the Harvard Graduate School of Design at a late age of thirty-five.

Even before formalizing his architectural education, he was appointed as the youngest director to head MoMA’s architecture department in 1932. Johnson along with the historian; Henry-Russell Hitchcock toured much of Europe and brought together the four gurus of modern architecture: Le Corbusier, Walter Gropius, Mies van der Rohe and J J Oud in the most celebrated exhibition of the twentieth century titled, ‘The International Style.’ Johnson was so enthused being put in charge of such a worldly event that he entirely financed the exhibition at no cost at all to the Museum. Despite his philanthropic accountability [with his father’s generosity] at the youthful age of twenty-six, he managed to infuriate Frank Lloyd Wright who chose to be excluded from this first of its kind spectacle of a show which drew a crowd of thirty-three thousand design enthusiasts in six weeks. His timely telegram to Johnson read…

“My way has been too long and too lonely to make a belated bow to my people as a modern architect in company with a self-advertising amateur [Raymond Hood] and a high-powered salesman [Richard Neutra]. No bitterness and sorry but kindly and finally drop me out of your promotion.” (1)

[1] The International Style Exhibition, MoMA, New York. [1932]

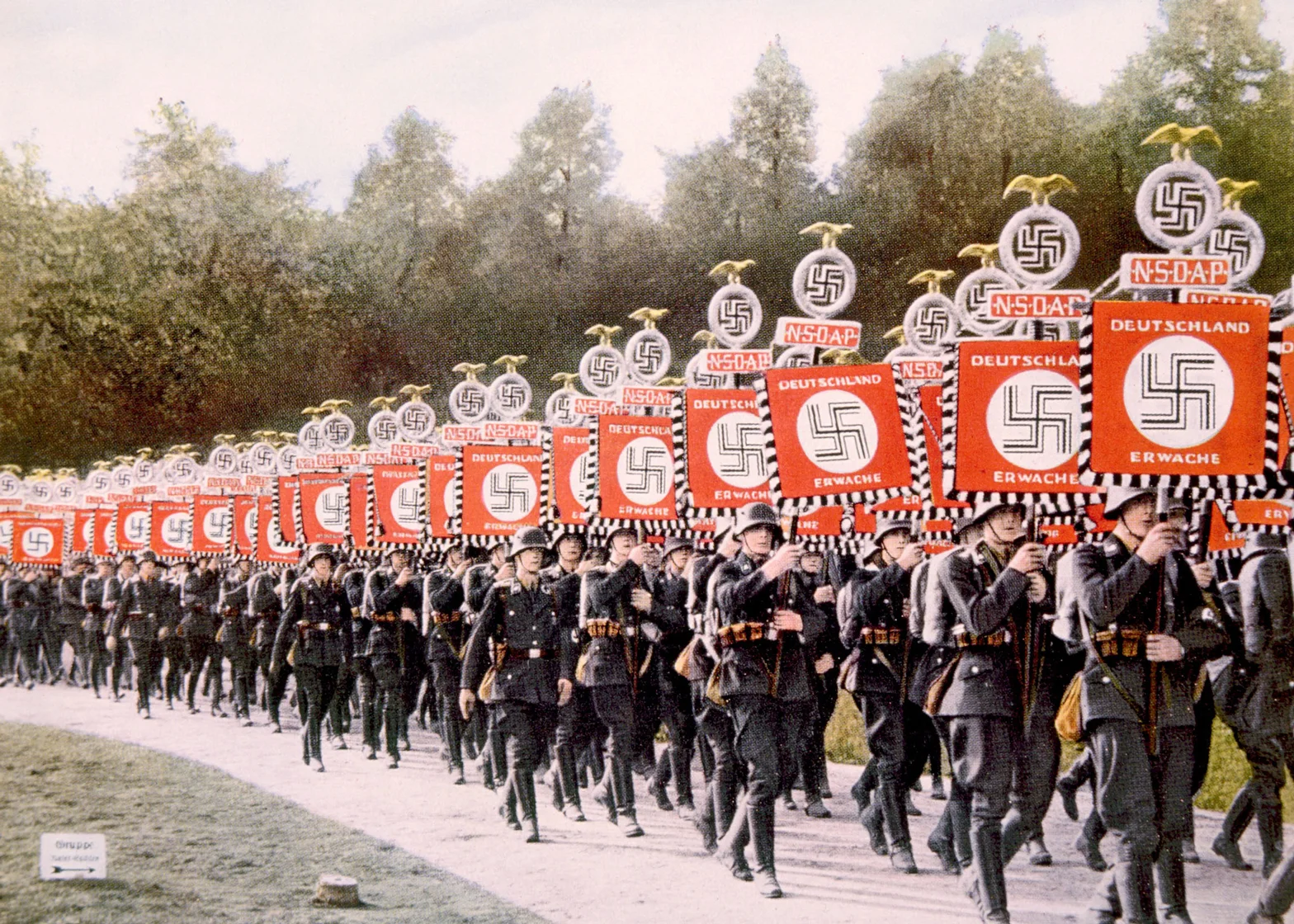

Upon leaving MoMA, Johnson frequented Europe and particularly travelled to Berlin, attending youth rallies organized by the Third Reich. The American journalist, Marc Wortman wrote in his book, Grove Atlantic: “Johnson was an impassioned supporter of Nazism, in which he found a ‘new international ideal’; where the aesthetic power and

exaltation he experienced in viewing Modernist architecture found its complete national expression in the Hilter-centred Fascist movement.” (2)

[2] Portrait of Philip Johnson by B Pietro Filardo

Wortman in his book, also continued to reveal that Johnson would file war reports to an anti-Semitic newspaper, comparing the Nazi rallies to be as much a spectacle as a Wagnerian opera with performances that celebrated artistic visions of aesthetics, eroticism, and war, - forces capable of sweeping away the past and building a new world order. (3) In the meantime, back home in the United States – Johnson started to become a household name for his pro-Nazi propaganda, hence not to his advantage began to seek the much un-needed attention of the Federal Bureau of Intelligence. In 1940, with continuous persecution from his friends, Johnson decided it was time for a total social reform. At the age of thirty-four he enrolled into the architectural graduate programme at Harvard GSD, where Wortman writes, “Johnson always wanted to be on the winning side.”

[3] Nazi SS troops marching with victory standards at the Nazi party’s annual rally in Nuremburg [1933], which Philip Johnson attended five years later.

[4] Mies van der Rohe, Farnsworth House, Plano, Illinois [1951]

The peculiarity that revolves around this controversy is that here we have two houses which have been the greatest source of inspiration since the mid-twentieth century, where one was conceived sooner, then the other that was built first. The Farnsworth house took six years [1945-1951] to complete with the normalclient, neighbourhood and city approvals and cost hindrances. The project was ill-fated terminating with a law-suit that left Mies with a bitter victory and an unfinished house. The Glass house on the other hand was fully completed to every detail in two years [1947-1949] with no budget, no cost overruns and no neighbours to deter approvals and the architect was the client. The specifications for the large sheets of glazing were achieved in the Glass house which was value-engineered in the Farnsworth house. One has only to compare notes to establish the truth; fame follows fortune.

The condemnation by the critics was often not over the misuse of the design [by Johnson] but rather the injustice over matters of exactitude to the ideal it was to have been duplicated. Even in a publication that is tribute to the fame of the two houses Sylvia Kavin writes, “For some observers, a more proper name for the Johnson house would be ‘After Mies’ or ‘Mies by Johnson.’ Like a precocious work of Postmodern appropriation.” (5)

And from Johnson himself: “Mies thought the workmanship was bad, that the design was bad, that it was a bad copy of his Fransworth House which had inspired me. He thought I should have understood his work better.” (6)

[5] Philip Johnson, Glass House, New Canaan, Connecticut [1949]

With his parents’ highbrow affiliations, Johnson was immediately granted commissions upon his graduation for numerous private homes where his main source of inspiration was always from his mentor, Mies. At that time, it was not that apparent nor was anyone too bothered by the similarities of the architectural vernacular between Mies’s works to Johnson’s. There was an intellectual sensibility toward universality in terms of form and details supported by a dialectic that validated the premise of ‘appropriation.’ This ‘getaway aesthetic’ was commonly accepted as a complementary aesthetic supported by a neutrally structural solution of a steel and glass assemblage on a steep incline. Arthur Drexler justifies this general acceptance by the profession in his book on Mies, “the Barcelona Pavilion is more than a unique masterpiece. It is the grammar of a complete style, an ordering principle capable of generating other works of art.” (7)

[6] Mies van der Rohe, Hillside House Sketch [1933]

[7] Philip Johnson, Leonhard House [1956]

What on earth causes these distinguished architects to make design suggestions that a talentless, comic strip-besotted schoolchild could devise in the course of a few moments of idle doodling. (8)

[8] Philip Johnson with John Burgee Architects, Hines College of Architecture, University of Houston, Texas, 1985

It is bafflingly obvious that a famous or [more accurately], a socially and politically well-connected architect gets commissioned to design a school of architecture with only a shallow claim of appropriation as his inspiration.

[9] Top Left: Octastyle temple at the top of the Hines College of Architecture (1985), Philip Johnson with John Burgee Architects, Photograph: Burdette Keeland Architecture Papers, Courtesy of Special Collections, University of Houston Libraries.

[10] Top Right: Drawing of House of Education (Unbuilt) (1773-1779), Claude Nicolas Ledoux Architect

One can confidently claim that this blaringly obvious appropriation was a calculated attempt by Johnson to commodify architectural form beyond its true function, more as a rhetorical provocation than an aesthetic challenge and thus demonstrating [trickster] to students of the school to see [tease] architecture from another [his] point of view.

Johnson grew up accompanying his parents on their worldly travels, so art became an integral component to his education and life. As a prominent New York socialite, he would invite his friends who were artists, collectors and curators to his New Canaan Estate for weekend retreats and show his prized art collection. It comes as no surprise why art especially figurative art would play an important role in his buildings. His students in Pratt, Yale and Harvard were taught through design assignments to connect the tradition in the arts by studying the masters through imitation. He is remembered by his devoted students for his witty tease, “You don’t have the mental equipment as a student not to copy, so why disregard the originals?” (10)

[11] Artist: Muriel Castanis, Sculptures for Façade at 580 California Street, San Francisco (1984)

Peter Eisenman: Philip…You abhor the term “pastiche.” The fact is that with all these contradictions and your so-called indifference you are making a pastiche of a complex (One International Plaza) rather than a genuine complex: a plaza in which people do not enter, corners in which intersections are articulated inconsistently, a base that has four different string-course heights and really four different scales. You use the term “platonic solids” and then make a Palladian arched entry. There are so many questions that remain unresolved that I have to raise the question of pastiche.

- Philip Johnson

[12] Palladian curtain-wall façade, One International Place, Boston [1987]

The Curator of the The Glass House, Irene Shum invited Japanese artist, Fujiko Nakaya to install the Estate’s first site-specific artist project. ‘Veil’ revealed a dialectic to a time-based ‘tension’ between an opaque atmosphere and the building’s transparency creating another form of timelessness which was something Johnson spoke much about – the balance of the opposites. The temporal effects of the installation brought another type of architecture that vanishes to return again and vanishes and only to return again.

[14] Fujiko Nakaya: Veil [2014]

[15] Yayoi Kusama: Dots Obsession – Alive, Seeking for Eternal Hope. [2016]

Photo by Matthew Placek

Johnson had admired and collected Kusama’s work and hence it was the curators intend to reconstruct that celebratory spirit, so often experienced and enjoyed by guests and friends who frequented his home for the past sixty years.

- T.S. Eliot

[16] Philip Johnson, Week’s Cover, January 8, 1979

“… it is considered decadent and even distasteful to experience nor display any form of indulgence while conducting oneself in the practice of architecture and yet the ancient idea of pleasure still seems sacrilegious to contemporary architecture.”

In 1976, Tschumi moved to New York to begin a prolific decade of drawings and writing theoretical texts that to his critics were more representative of contemporary art and film than architecture, hence labelling his work as ‘impure.’ (11) He was thirty-two and he had no built projects but he had begun to invent new ways of comprehending and representing architecture that drew from other sources such as philosophy, literature, art, film, and even advertising. Yes, advertising. He developed a series of ‘conceptual landscapes’ which he called, ‘Advertisements for Architecture’ derived from a vocabulary indicative of propaganda and advertising. Tschumi was teasing his peers then with a form architectural manifesto that was consistent with a particular type of historicism and gene that he wished to be associated with. It was obvious that Tschumi set out; ‘to shake-up static, inherited definitions of architecture and introduced notions of movement and social events into the supposedly pure realm of space. The Advertisements were also intended to function the way advertising always does – by triggering seduction and desire.” (12) In the late seventies, Tschumi was notorious for tapping into surrealism as a medium in architecture; creating illusions and concealing identities, often fantastical and apocalyptic.

[18]

[18]

[19]

Tschumi always had a partiality towards performance art [i.e. dance + theatre], once he created a provocative drawing describing it to be based on a very complex tango step [Image 20] which was how he viewed his relationship to constraints: “As in judo, it is about using the opponent’s own strength to defeat him.” (13)

[20]

Twenty-seven years after this tease of how he would theoretically overcome constraints, “Tschumi engaged a judo-like match against the Planning Department and the New York City Zoning Codes” (14) – with a radical reconfiguration [trick] from the traditional terracing often identified with apartment buildings on the Lower East Side, New York. A crystalline form pierced the LES skyline, a ‘BLUE’ residential tower was conceived; marking Tschumi’s first urban manifesto - ‘L.E.S. is More!

[21] Blue Residential Tower, Bernard Tschumi Architects, New York, 2004-2007

In 1988, Tschumi struck a double-bill in his career. He took office as the new dean of Columbia’s GSAPP and across the Atlantic, La Villette commenced into design phase with a pair of draughtsmen on his payroll. While his peers in the academia were rewriting modernism, classicism and historicism, he on the other hand was rewriting [the] words and only his writings dominated his stage! He was not concerned about constructing buildings but rather constructing new directions in architectural thought, probing literature and language as catalysts. La Villette was aimed at an architecture that meant nothing, an architecture of the signifier rather than the signified – one that possessed a pure trace or play of language. (18)

[22]

[23]

“The agreement between thought and reality consists in this: that if I say falsely that something is red, then all the same, it still is not red. And when I want to explain the word “red” to someone, in the sentence ‘That is not red,” I do so by pointing to something that is red.”

RED IS NOT A COLOR

“I [Tschumi] am frequently asked, “Why are the folies red?” And I say, “I never answer that question.” Then I started to think that each project has a concept. The issue is how to reinforce the concept. I decided that the use of color would be a means of reinforcing the concept. So, when I answered, “Red is not a color,” I meant it to be more than provocative. For me, it is about what makes architecture concepts.”

“Madness would then be a word in perpetual discordance with itself and interrogative throughout, so that it would question its own possibility, and therefore the possibility of the language that would contain it; thus, it would question itself, since the latter also belongs to the game of language.”

Madness serves as a constant point of reference throughout Parc de la Villette wherein Tschumi chose to demonstrate new social situations by introducing a post-structuralist philosophy and accentuating the double meaning of the word folie. Through his highbrowed allies, young Tschumi was introduced and animated by Derrida’s intellectual sparks in the use of ‘negative grammar’ made up of - dissociation, dislocation, disjoining, disassociation, and deconstruction, with the aim of questioning ‘the things that hold together,’ all the while recognizing the paradox that architecture and the ‘enigma’ of the work, the signature, is still after all ‘what holds together that which is not held together organically.’ Tschumi [always] successfully draws out the mischief in language. (19) Madness, here is linked to its psychoanalytical meaning – insanity [in French]; where Tschumi attempts to free the built folie from its historical connotations. For Tschumi, ‘architecture needs mechanisms that allows it to become connected to culture.’ (20) And language for Tschumi are his ornaments in his architecture.

Subjective in Architecture

This short essay is an attempt to establish the forces that have shaped the practice of architecture, which were often driven by the engines of commerce fuelled by neoliberalism in the face of rationality and truth. Forces that been in conflict since antiquity when the Classical | Truth were debated right up to our contemporary times, where the Personal | Ideal is critiqued. I trust that the narrative and the visuals presented through the two canons of architecture clearly demarks that subjective in architecture is quite circumscribed. In the realm of neoliberalism, it certainly spells out that to achieve the ideals in architecture and/or utopia; you either pay for it yourself by being your own ‘bank’ [and confront the criticisms later] or you keep writing ‘books’ about it till everyone agrees!

| Philip Johnson | was a rarity but more importantly he was a ‘natural’ because there was no pretence in any of his grandiose endeavours as an architect. The fact that he was convinced at a very young age that consensus will never ever earn him the truth in obtaining the ideal, he resorted to the only two things that society-at-large will surrender to - the American way, Capitalism + Ego. It is what won the people of America their president in the 2016 elections, the Trump way or no way at all!

| Bernard Tschumi | on the other hand resorted to the European paradigm, through the liberal arts which in its present construct is the greatest force in neoliberalism. It is not as tall as the cathedrals of commerce because in the current paradigm, architecture’s materiality is a composite one, made up of visible and invisible forces. but it penetrates and holds captive the ‘mass consensus’ who seek contentment by staying abreast with the Information Age!

[2] http://www.connecticutmag.com/the-connecticut-story/the-hidden-nazi-past-of-famed-architect-philip-johnson/article_6488b3fa-b1cf-11e6-929a-cb0225b08e0e.html

[3] Image courtesy of Shutterstock.

[5] https://homeadore.com/2016/03/03/glass-house-philip-johnson/

[6] https://www.pinterest.com/pin/156007574567926299/

[7] http://www.ncmodernist.org/pjohns10.gif

[8] Photograph courtesy of Richard Payne

[9] Bjone, Christian, Philip Johnson and His Mischief, The Images Publishing Group Pty Ltd, 2014. P.6

[10] Bjone, Christian, Philip Johnson and His Mischief, The Images Publishing Group Pty Ltd, 2014. P.7

[11] Bjone, Christian, Philip Johnson and His Mischief, The Images Publishing Group Pty Ltd, 2014. P.55

[12] Bjone, Christian, Philip Johnson and His Mischief, The Images Publishing Group Pty Ltd, 2014. P.4

[13] http://architizer.com/blog/the-seven-deadly-sins-of-postmodernis

[14] http://www.bassamfellows.com/entry.html?id=24

[15] http://theglasshouse.org/whats-on/yayoi-kusama-narcissus-garden/#

[16] http://content.time.com/time/covers/0,16641,19790108,00.html

[17] http://www.we-find-wildness.com/2010/12/bernard-tschumi-advertisements-for-architecture/

[18] http://www.we-find-wildness.com/2010/12/bernard-tschumi-advertisements-for-architecture/

[19] http://www.we-find-wildness.com/2010/12/bernard-tschumi-advertisements-for-architecture/

[20] http://www.bauwelt.de/themen/bilder/Bernard-Tschumi-2118501.html

[21] http://www.designbuild-network.com/projects/blue-tower/blue-tower1.html

[22] http://davidhannafordmitchell.tumblr.com/image/139026937223

Spencer, Douglas, The Architecture of Neoliberalism, 2016

Bjone, Christian, Philip Johnson and His Mischief, 2014

Bayrle, Thomas | Zybach, Andreas, Layout Philip Johnson, 2003

Stern, Robert A. M., The Philip Johnson Tapes, 2008

Tschumi, Bernard, Architecture and Disjunction, 1996

Tschumi, Bernard, Architecture Concepts. Red Is Not A Color, 2012

Eisenman, Peter, The End of the Classical, 1984

Tafuri, Manfredo, Architecture and Utopia, 2012

Jameson, Fredric, Postmodernism, or The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism, 1992

Moussavi, Farshid | Kubo, Micheal, The Function of Ornament, 2008

Lavin, Sylvia, Kissing Architecture, 2011

Kaprow, Allan, Assemblage Environments + Happenings, 1965

Tschumi, Bernard, La Casa Vide : La Villette, 1985

Tschumi, Bernard, The Manhattan Transcripts, 1994

TERM TWO